The Election Administration and Voting Survey – Purpose and Limitations

The Election Assistance Commission (EAC) released the 2020 biennial Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS) results. The EAC administers the EAVS to state election officials, who provide aggregated administrative election data. That data is analyzed by the EAC, researchers, and election officials to better understand the voting process—including voter registration, voting equipment, poll workers, polling locations, and a variety of other topics. EAVS is an important mechanism providing a source of data that is unavailable anywhere else.

As important as the EAVS is, there are still issues with the data that is supplied. For example, election administrators report that EAVS questions are often confusing and attempt to translate practices that vary widely across localities to standardized categories. As a result, administrators may be asked to supply answers to questions that are not applicable to their locality. While we have seen steady improvement in the level of data completion of the data sets, there is still work to be done.

As Jack Williams, Senior Researcher at MIT Election Lab, noted in a recent article, “(The EAVS) is the most valuable in getting a national perspective on how Americans vote. Still, it’s no substitute for the administrative data maintained by the states themselves, which often differ from EAVS for many reasons that are justified.”

The EAVS Section B Data Standard – Purpose and Added Value

A comprehensive analysis of administrative election data stands to provide critical insight into effective policies. At this time, the EAVS can only provide limited information due to the nature of aggregated date and, at times, ambiguous questions subject to interpretation by election officials. The Council of State Governments Overseas Voting Initiative (OVI) is dedicated to improving the process of voting for military and overseas citizens and intends to use the implementation of the EAVS Section B (ESB) Data Standard as a catalyst to do so. We wrote more about the development of the ESB Data Standard here.

Section B of the EAVS collects data about military and overseas citizen voting. There is a wealth of knowledge that can be gleaned from this data, especially if collected at a transactional level. The ESB Data Standard does just this. This standard allows us to dig deeper into the data than EAVS, thus providing us with a better understanding of what can lead to either voting success or voting failure among military and overseas citizens.

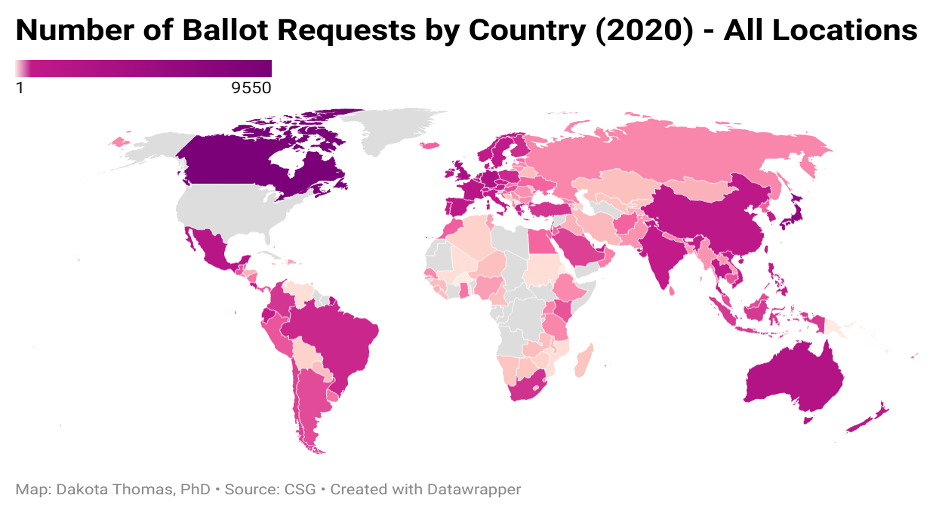

More than that, the data can point to opportunities for further research. This would involve meeting with states and local jurisdictions to better understand what the data is showing. For example, perhaps we suddenly see a sharp decline in the rejection of ballots due to a missing voter signature. This could be caused by any number of things—more effective voter education, a new curing policy, a different set of instructions included with balloting materials, or just sheer luck. Upon speaking with election officials, we could determine if there was a particular action that yielded this result and highlight these findings for jurisdictions interested in doing the same. As another point of analysis, the ESB Data Standard can help officials mitigate the ever-changing difficulties of mail delivery during a pandemic. Data gathered according to the Standard can determine where a voter is located overseas , where a mail service disruption(s) took place, and if the mitigating strategies put in place were successful . This information is collected through multiple data fields of the Standard such as a voter’s mailing country. A visualization is provided below demonstrating the number of ballot requests by country. This figure was generated using the ESB data provided by a subset of working group members who have implemented the standard in their local context.*

It is important to work with the election officials to not just understand what is in the data set, but “the why” behind that data. Because EAVS is asking very specific questions that are at times confusing to election administrators, the full story behind the data is sometimes lost. Our goal with our project is to ensure that we are asking the why, as that can better inform reflections on policy changes.

Additionally, the work election administrators put into completing the EAVS is extremely burdensome. Often, states must enlist the help of local election officials to answer some parts of EAVS. These officials often have limited resources and, in many cases, numerous other job duties in addition to election administration. Our hope with the ESB Data Standard is that, upon creating either a database query or a report that aligns with the standard, it will be easy for election officials to pull all relevant transactional data with little effort.

Adaptability of the Standard

What is most exciting about the ESB Data Standard is its adaptability. Because the standard was designed to accommodate both traditional absentee voting models and vote-by-mail models, it can easily be modified to capture EAVS Section C data. EAVS Section C deals with all other by mail voting from absentee voting (other than military and overseas citizens), permanent absentee voting, to by-mail voting. As such, the structure of the ESB Data Standard already aligns with Section C of the EAVS.

Development of the Standard

The ESB Data Standard was developed in collaboration with election officials. Through soliciting their insight, the Standard was designed to incorporate the data that jurisdictions currently collect as well as the data that are central to a comprehensive understanding of the voting process. The OVI has also worked with election officials in one state to map processes pertaining to how military and overseas citizens register to vote, request their ballot, and vote their ballot. Such work revealed where the state’s database system captured or failed to collect ESB data points. The OVI also learned that some data points were captured and maintained outside of the state database, helping to explain why certain data points were not available in our research.

Overall, the EAVS provides us with a wealth of information. However, we believe that leveraging data standards such as the ESB Data Standard is a worthwhile investment. These standards allow us to acquire transactional level administrative data directly from the states in a manner that is less time consuming, creates less ambiguity in the data responses from election officials, and provides a more robust data set to analyze.

*The map was generated with the data from Colorado, Washington, Orange County, and Los Angeles County, and excludes records where the mailing location was the United States.