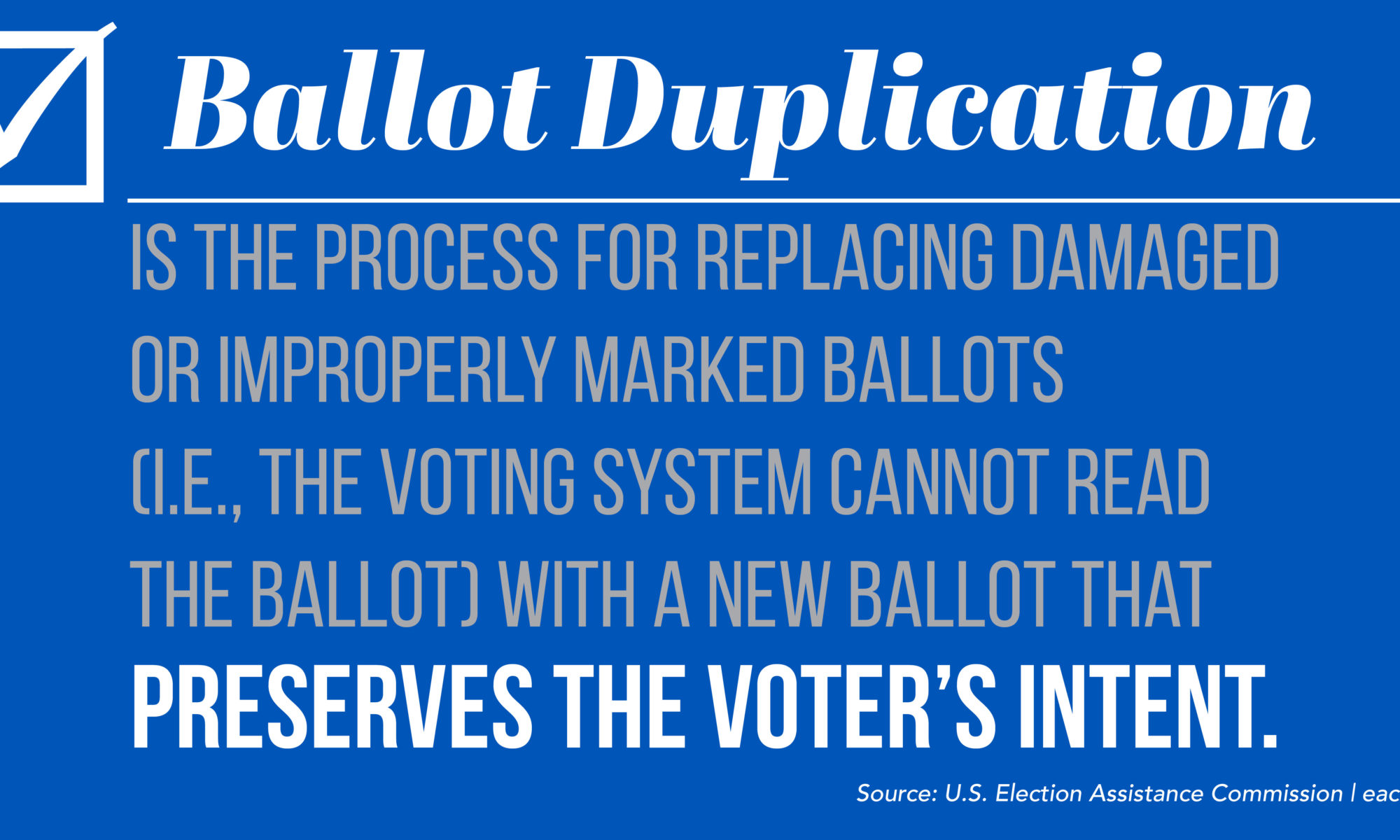

With the November 3, 2020 election in the nation’s rearview mirror, it is time to examine some of the challenges that affected military and overseas ballots the Overseas Voting Initiative (OVI) discussed in the lead up to the presidential election.

One such topic is ballot duplication. In the coming weeks, the OVI will examine:

- noteworthy instances of ballot duplication that occurred last fall;

- implementation of new automated ballot duplication systems and how they fared;

- in-person and remote observation of ballot duplication and post-election processes during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions; and

- ideas for improvement to the ballot duplication process going forward.

Last summer, the OVI issued a series of articles regarding ballot duplication and providing timely recommendations for election officials to consider in 2020. It was anticipated that the pandemic would result in an increase in the use of absentee, by mail and other ballots cast outside of polling places. This, in turn, would necessitate an increase in duplication.

In fact, the topic of ballot duplication was discussed frequently by election officials and in the media as voting procedures were a focus of post-election analysis.

Election officials across the country, including those in Montgomery County, Maryland, Marin County, California, and San Joaquin County, California, proactively shared information with their communities and the media on their processes for duplicating damaged or otherwise machine-unreadable ballots prior to November 3, 2020. The Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) even highlighted the ballot duplication process preemptively – and cited the OVI’s article series – in its highly-referenced “Rumor Control” website explaining that, “In some circumstances, elections officials are permitted to “duplicate” or otherwise further mark cast ballots to ensure they can be properly counted.”

Despite the diligent work by election officials and others to explain the nature and purpose of ballot duplication, the topic was still a subject of considerable misinformation and disinformation [1] post-election. For example, officials in Delaware County, Pennsylvania were forced to debunk manipulated video of their ballot duplication process and City of Detroit election officials testified about the process to their state senate.

Perhaps most notably, Maricopa County, Arizona authorities worked to explain and combat ballot duplication misinformation and disinformation that quickly spread on social media. This was focused on proper vs. improper methods for marking paper ballots and concerns about whether these ballots would be counted. This became known as “Sharpiegate.” It was featured in CISA’s Rumor Control site, again referencing the OVI series on ballot duplication.

Additionally, there were stories about jurisdictions utilizing the ballot duplication process for ballots affected by the following notable circumstances:

- Ballots with Printing Errors – In Tarrant County, Texas, election workers had to duplicate one-third of the jurisdiction’s absentee ballots due to a printing error that rendered bar codes illegible on approximately 20,000 ballots. Ballots in Outagamie County, Wisconsin contained a misprint visible in a black square — known as a timing mark — near the edge of the ballots. The misprint necessitated the duplication of 13,500 ballots so ballot machines could read them accurately.

- Burned and Water Damaged Ballots – 2020 saw ballot drop boxes set on fire in Boston and Los Angeles. In Boston, there were 122 ballots inside the drop box when it was set on fire, only 87 of which were legible and able to be counted, though it is likely some fire-damaged ballots required duplication to go through ballot scanners. In Los Angeles, another ballot drop box fire resulted in over 200 damaged ballots left in a seared, soggy pile. Election officials had to sift through these to see what could be saved, again, likely using ballot duplication procedures. In both instances, voters whose ballots were not able to be saved received replacement ballots.

- Braille and Large Print Ballots – Election jurisdictions offer a variety of assistance and services to aid voters with accessibility challenges. In some jurisdictions, like counties throughout Arizona, Braille and large print ballots are offered to voters. Prior to the November 3 election, Maricopa County election officials received requests for 26 Braille ballots and 555 large print ballots, all of which needed to be duplicated upon return before they could be counted. While duplication of Braille and large print ballots was not new in 2020, extensive discussion of it was.

The next article in this series will cover how ballot duplication and other post-election processes were viewed by both in-person and remote election observers while dealing with physical distancing, building capacity restrictions, and other COVID-19 restrictions.

[1] Misinformation is false information that one spreads because they believe it to be true. Disinformation is false information that one spreads even though they know it to be false. The difference between the two is intent.