If there is one constant in election administration, it’s change.

Election officials are constantly innovating to meet the evolving needs of voters. Voter portals, “one-stop self-service” sites, enable voter access to individualized voting materials.

Vermont’s election portal, called My Voter Page or MVP for short, provides a web-based data search interface of information extracted from Vermont’s statewide voter registration database. MVP provides a web-based data search interface of information extracted from Vermont’s statewide voter registration database.[2]

MVP was first introduced to Vermont’s voters for use in the Nov. 8, 2016 election by Jim Condos, former Vermont Secretary of State.

In early 2015, the Vermont Secretary of State’s office initiated an 18-month development and implementation plan for the voter portal as part of a larger Election Management System solution. Election management and portal development began after a competitive procurement process resulting in the selection of a PCC Technology Group, LLC, now known as Civix, the state’s collaborator.

Elections in Vermont are conducted at the township level by 247 town clerks. According to Will Senning, Vermont Director of Elections, building an election management system stemmed from a desire to include an individualized hub for a voter’s information and allow each voter to interact electronically with their specific clerk. The portal allows voters to view their sample ballot, respond to a National Voter Registration Act notice, request an absentee ballot, check that the request was received and view the absentee ballot issue date and the date the clerk received the ballot.

From the outset, Vermont’s MVP allowed all Vermont residents to electronically register to vote, take the voter oath, review or respond to any voter challenge letters, find their elected officials and check their:

- Voter registration status

- Absentee ballot status.

- Mail-in application and ballot status.

- Poll location.

- Registration information on file with the town office.

- Sample ballot for the upcoming election.

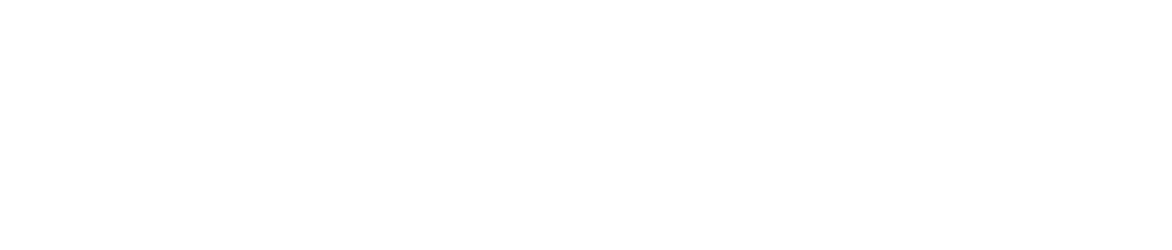

Portal Use for Vermont’s Military & Overseas Voters

This includes all Vermont military and overseas citizens covered by the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA). On Aug. 29, 2016, Condos told Vermont Business Magazine,

“Voting for our military and overseas voters is now easier than ever. It is my pleasure to present this information [about MVP] to help these Vermonters register and vote.”

Through MVP, Vermont’s military personnel and overseas citizens can easily participate in the election process by registering to vote and requesting a blank ballot online. In Vermont, voters covered by UOCAVA must return their ballots by mail. However, they may request their ballot by phone, fax, email or mail. They may also request that their unvoted blank ballot and certificate for the return envelope be delivered to them electronically via MVP. Voters who request delivery of a blank ballot through MVP receive an email generated by the system stating their ballot is available and providing them with a login. The voter can access the ballot through MVP and either mark the ballot through onscreen marking before printing, or hand mark the ballot and then return it by mail. Per UOCAVA, any ballot requested more than 45 days before the election will be mailed on the 45th day before the election. This means that if the blank ballot is sent electronically the voter would receive it immediately, allowing them more time to return their completed ballot.

Accessible Voting and Vermont’s Portal

According to Vermont’s Election Division website, “Vermont’s election laws are designed to make it easy for all eligible Vermonters to vote and to register to vote. One of the specific purposes of the Vermont Election Laws is ‘to provide equal opportunity for all citizens of voting age to participate in political processes.’”

In 2018, after a competitive procurement process, a new accessible voting solution was introduced by the Vermont Secretary of State’s office. This solution – OmniBallot – is a tablet-based ballot marking system that marks the voter’s selections onto paper ballots, increasing the privacy and independence of a voter with disabilities. OmniBallot also contains an online interface that enables citizens with disabilities to vote from home during the early voting period.

Post-Pandemic Voting by Mail and the Portal

After experimenting with vote-by-mail procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic, Vermont joined California, Colorado, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Utah and Washington to become one of eight states that now conduct elections almost entirely by mail.

As a result of a 2021 Vermont law, all active registered voters in Vermont are now mailed a ballot for each general election, unless they have requested that their ballot be electronically delivered via their MVP. All Vermont voters are able to cast an absentee ballot if they so choose. Vermont voters can return their ballots via mail, in-person at their town or city clerk’s office, via secure ballot drop box before Election Day or at their polling place on Election Day.

Vermont’s My Voter Portal conveniently and securely facilitates voter registration, viewing of a sample ballot, electronic ballot delivery, ballot tracking and more. It is a valuable tool supporting Vermont’s new vote-by-mail process and for the state and local election officials who serve voters – including military and overseas Vermonters worldwide, and voters with accessibility challenges .

[2] MVP is not the official record of a voter’s registration. Voter registration records are retained by each person’s voter registration office in the specific Vermont town where they reside at https://mvp.vermont.gov/.