Casting a Ballot: Challenges Faced by Overseas Voters

In 2016, the Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP) conducted the biennial Overseas Citizen Population Analysis. This analysis indicated that there were approximately 5.5 million uniformed military and overseas citizens living abroad, of which 3 million were eligible to vote.

These individuals, commonly referred to as UOCAVA voters, face a unique set of challenges when attempting to cast their ballots. Communication between these voters and local election officials may be hindered by remote deployments or lack of access to reliable phone and/or internet connections. For those who are required to scan and fax their completed ballots, access to the necessary technology may also be a significant barrier. As with stateside voters, the impact of these barriers depends on an individual’s unique circumstances, which are often difficult for elections administrators to isolate and address.

Elections Administration Voting Survey, Section B

Despite these difficulties, the overall impacts of such challenges on UOCAVA voters are well-documented. Every two years, the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) carries out the Elections Administration Voting Survey (EAVS) – a survey of how states conduct federal elections. In Section B, the survey specifically seeks to identify UOCAVA voters’ overall successes and failures. For example, in the 2018 general election alone, 655,409 ballots were transmitted to UOCAVA voters. Of these ballots, only 338,271 (approximately 52%) were received and counted.

Although the EAVS helps shed light on overarching trends in the UOCAVA voting process, it is unable to isolate and identify key factors at the transactional level that contribute to voting success or failure. In their 2017 report, Using Technology to Enhance Military & Overseas Voting Vol. 2: Recommendations for Use of Data Standardization and Performance Metrics, the Overseas Voting Initiative outlined various factors that inhibit those analyzing this information – namely the Federal Voting Assistance Project (FVAP) and the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) – from doing so. Two factors stand out:

- The EAVS Section B only collects aggregated data. This data is not only difficult to collect but also lacks context of individual voter experiences, which may help shape state and local policy.

- State and local elections jurisdictions supplying this data lack a uniform method for collecting, sharing and analyzing data[1].

Developing the EAVS Section B Data Standard

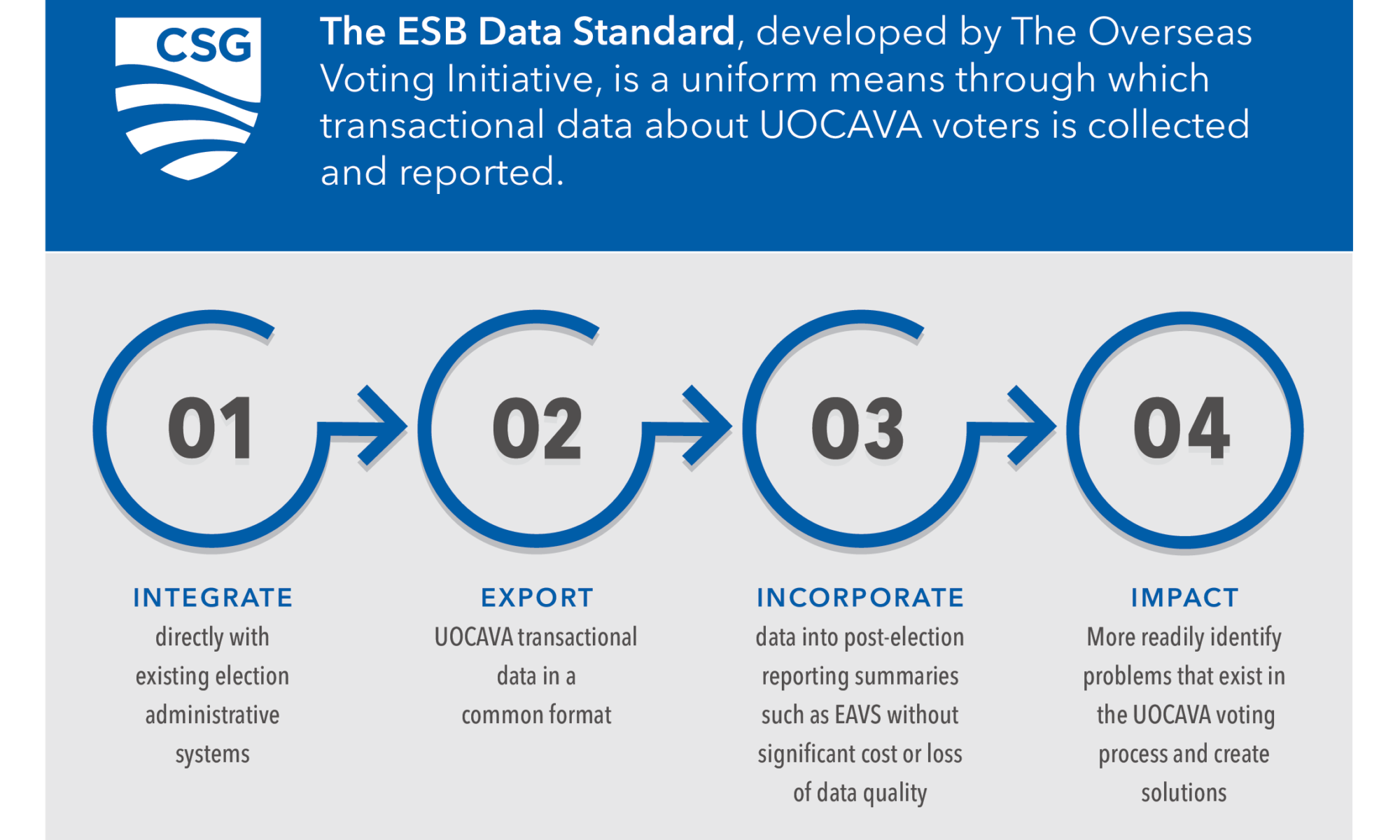

Based on these factors, The Council of State Governments and various technology working group members recommended the development and implementation of the EAVS, Section B (ESB) Data Standard. This standard effectively captures and stores transactional level data about an anonymized individual’s voting experience, including:

- The ballot’s country of destination;

- The date a voter was sent their ballot;

- The mode of ballot delivery and return;

- The date the ballot was received by the local election office, among others.

Benefits of the ESB Data Standard

By integrating the ESB Data Standard with existing election administrative systems, election officials can not only better identify the length of time between a ballot request and its return, but also the key factors contributing to voter failure. These aspects can then be addressed, and UOCAVA voting outcomes improved. Additional benefits of the data standard include:

- Easing reporting requirements faced by election officials;

- Facilitating the identification of jurisdiction best practices and thus the provision of better service to UOCAVA voters;

- Reducing errors, inaccuracies and administrative costs associated with data collection and leading to a more efficient and effective process for UOCAVA voters;

- Generating reliable information to be used in potential post-election disputes or recounts

Implementation

Since 2016, the Overseas Voting Initiative (OVI) and its advisors have conducted state outreach to explain the importance of the data standard and its potential benefits. Jared Marcotte, Senior Technology Advisor to the OVI and Founder of The Turnout, has been central to these efforts. Prior to conducting outreach, Marcotte was instrumental in conceptualizing and developing the standard. His work on the Voting Information Project directly informed the OVI’s approach to data collection.

Thanks to OVI’s outreach, 11 jurisdictions have already supplied the information necessary to implement the standard—with more to come. California (Los Angeles, Orange and San Diego County), Colorado and Washington have also agreed to participate in the first ESB Data Standard Roundtrip Pilot. As participants, these states will work closely with The Turnout and fellow OVI staff to fully implement the ESB Data Standard in their jurisdictions. By March of 2021, a case study will be produced examining the success of the pilot.

As outlined in The Council of State Governments 2017 report on data standardization and performance metrics, Iong-term sustainability of the ESB Data Standard will be crucial for ensuring its overall success. This will require continued collaboration between FVAP, the EAC and the National Institute of Standards and Technology to establish data repositories and related standards. Upon completion of the pilot, FVAP should also share best practices and lessons learned to assist the EAC with reducing post-election reporting requirements.

For further information about the Data Roundtrip Pilot or implementing the ESB Data Standard in your jurisdiction, please reach out to the OVI team or email [email protected].

[1] For a more in-depth discussion regarding the ESB Data Standard, please refer to The Council of State Governments’ 2017 report, Using Technology to Enhance Military & Overseas Voting Vol. 2: Recommendations for Use of Data Standardization and Performance Metrics, and their 2016 report, Recommendations from the CSG Overseas Voting Initiative Technology Working Group.