By Grace Gordon, Research Lead and Project Manager

Introduction

Presidential primaries work in unique and complex ways for overseas voters. Overseas citizens can vote in either their state-specific primary or, in some cases, a primary explicitly for overseas citizens. However, registering to vote in a presidential primary specifically for overseas citizens does not constitute registration for your state’s upcoming elections.

Before the 2024 presidential election, all overseas voters should ensure their state voter registration is up to date. To do this, overseas voters must double-check with their state or local election office ahead of the UOCAVA registration deadline for November’s presidential election. To ensure they receive their ballot in time, these voters should register using the Federal Post Card Application (FPCA) or through the voters’ home state formal process.

Background

In 1986, Congress passed the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA). This act permitted “absent uniformed services voters and overseas voters to use absentee registration procedures and to vote by absentee ballot in general, special, primary, and runoff elections for Federal office.” All states have designated processes for overseas voters to register to vote and cast a ballot. While the methods differ from state to state, all states accept the Federal Post Card Application as a form of registration for federal elections. For presidential party primaries, there are different methods for overseas voters to register to vote and cast a ballot.

In general elections, known as presidential elections, voters vote in their home state and electors in that state cast their vote for president based on the popular vote. Party primaries differ from the general election in several ways. Instead of electors casting votes based on the election results in each state or territory, delegates cast votes at the party convention. Each party has a different process for selecting delegates. Most delegates for the Democratic convention are chosen based on proportional representation. Whereas the Republican party primary uses a combination of proportional and winner-take-all representation decided by the states. Democrats Abroad is an organization that conducts a Global Presidential Primary for all overseas voters registered with the organization. Democrats Abroad receives several votes at the Democratic National Convention, which are allocated to delegates based on the results of the Global Presidential Primary.

Overseas voters who want to register to vote in the Democratic primary have two paths. They can register directly with Democrats Abroad and have their vote count towards the Democrats Abroad delegate allocation, or they can register directly with their state and put their vote towards their states’ delegates. There is no organization equivalent for registered Republicans, and Republicans living overseas must register with their state to vote in the Republican Party Primary.

All voters must register to vote for the general election in their state regardless of their political party affiliation. Voters registered with Democrats Abroad in the primary must ensure that their state registration is active through the state absentee registration process or use the FPCA to register and cast a ballot.

FPCA and Voter Registration Processes

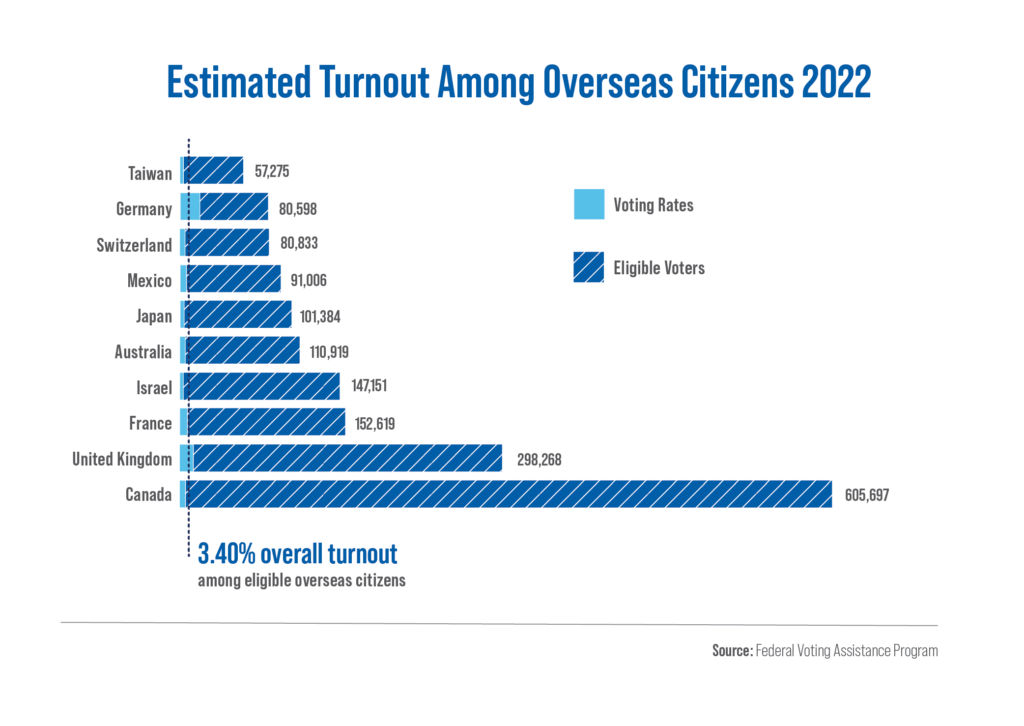

The FPCA offers a streamlined, easy-to-use voter registration and absentee ballot request form for overseas voters. In some states, the FPCA is accepted as an application to vote for all state and federal contests; in others, it is just a request for federal contests. To access the form, qualified voters can go to https://www.fvap.gov/uploads/FVAP/Forms/fpca.pdf.

Most state election websites offer detailed instructions on registering as a UOCAVA voter. The state or municipal voter registration process may offer another option for voters who prefer to register directly with their state rather than using the FPCA.

The Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP) has numerous resources for military and overseas voters seeking to register to vote in either the primaries or the general election. The following resources directly apply to this topic:

- How to vote absentee in the military: https://www.fvap.gov/military-voter/overview

- How to vote absentee from abroad: https://www.fvap.gov/citizen-voter/overview

- Voting assistance guides by state: https://www.fvap.gov/guide

- Voting residence for service members and their families: https://www.fvap.gov/military-voter/voting-residence

How to check your voter registration as an overseas voter

For overseas voters who cast a ballot in the primaries and are unsure if they are registered for the general election, the following steps can be used to check their voter registration in their home state:

- Do not rely on third-party groups to confirm voter registration status.

- Identify the state or local election office website, phone number or email.

- Contact an election official, ideally in the municipality where they are registered to vote. Some states offer a state voter registration lookup tool. In others, the overseas citizen will need to call or send an email to confirm their registration.

- Any overseas citizens who are not registered can register to vote in the primary using the FPCA or state/municipal voter registration process. The deadline to register for UOCAVA voters is 30 days before the general election for federal offices but varies for state and municipal elections.

Conclusion

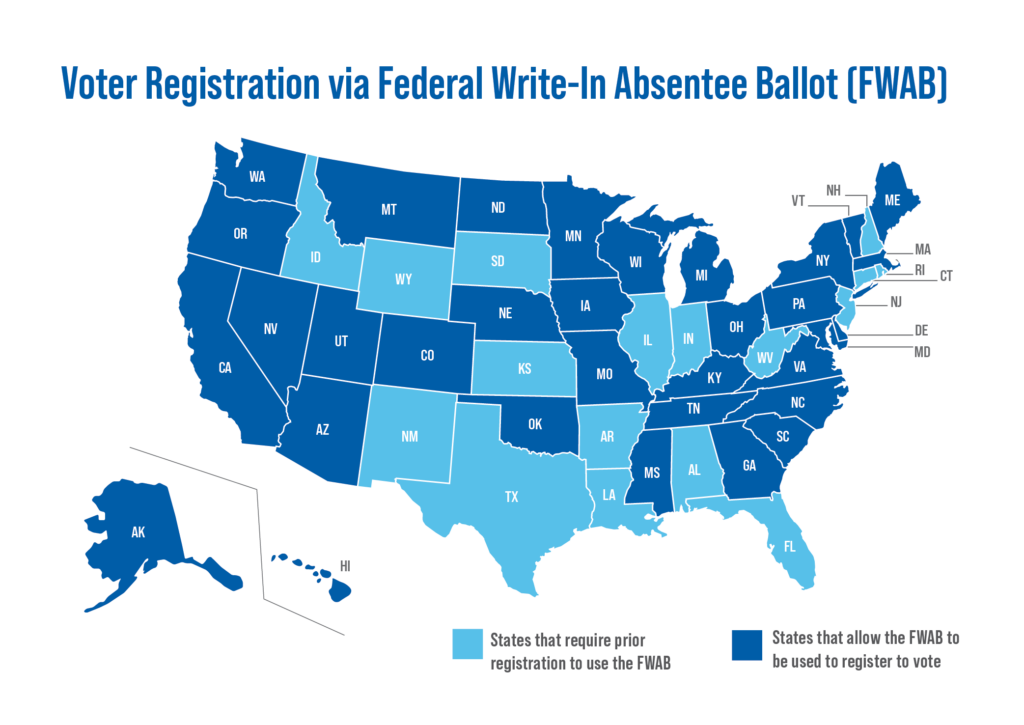

UOCAVA voters face extra hurdles when voting abroad. These include delays in international mail, difficulty accessing printers to print ballots or other election materials and challenges delivering their ballots back to their election office. Many states allow voters to fax their ballots back to the US, though access to fax machines continues to dwindle worldwide.

Election officials do everything they can to ensure UOCAVA voters have equal access to the ballot. Still, if a voter does not register to vote and indicate their international address, election officials cannot send them a ballot. To complicate matters, some overseas voters may vote in primary elections explicitly for overseas voters. Overseas voters who voted in the Democrats Abroad Global Presidential Primary must register to vote for the general election in their state. Registration with Democrats Abroad does not imply registration with a state for the general election. To ensure overseas voters who want to vote in the general election can do so, all overseas voters should double-check their voter registration as soon as possible.