Ballot duplication is a term well known to and commonly used by election officials throughout the U.S. This long-existing term — also known as ballot replication, ballot remaking and, less commonly but perhaps most accurately, ballot transcription — may sound a bit mysterious or perhaps downright nefarious to those not involved in the day-to-day intricacies of state and local election administration.

In the midst of a presidential election cycle, it is important to explain this sometimes misunderstood term and demystify it. Now, more than ever, a thorough understanding of this process is important, especially as all election processes receive extra attention and focus from the public, media and other stakeholders as we approach November. Ballot duplication remains a critically important concept for election officials in 2020 and beyond, and it is important to understand why.

The Council of State Governments Overseas Voting Initiative (OVI) Working Group of state and local election officials studied and issued recommendations to improve ballot duplication for state and local election officials with military and overseas ballots as the focal point in 2016. In 2017, OVI expanded on these recommendations.

In all states, Washington, D.C., and the five U.S. territories, groups of voters who meet certain jurisdictional qualifications can cast remote ballots using a vote-by-mail or absentee voting process. Many of these voters are military and overseas voters covered by the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) who do not have the option to vote in person within their voting jurisdiction in the U.S. With the passage of the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment Act, all UOCAVA voters can receive their ballots electronically — typically via email or an online portal. Additionally, some states allow ballots to be returned electronically, most commonly by email, via portal and fax.

What is ballot duplication?

According to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC), ballot duplication is the process for replacing damaged or improperly marked ballots (i.e., the voting system cannot read the ballot) with a new ballot that preserves the voter’s intent. The ballot duplication processes create a “clean ballot” with the voter’s choices that can be read by ballot tabulation equipment. The process also ensures that the original voter-marked ballot is retained for the record including any required auditing. It is the duplicated or transcribed “clean ballot,” and not the damaged one, that is counted by tabulation equipment.

Why conduct ballot duplication?

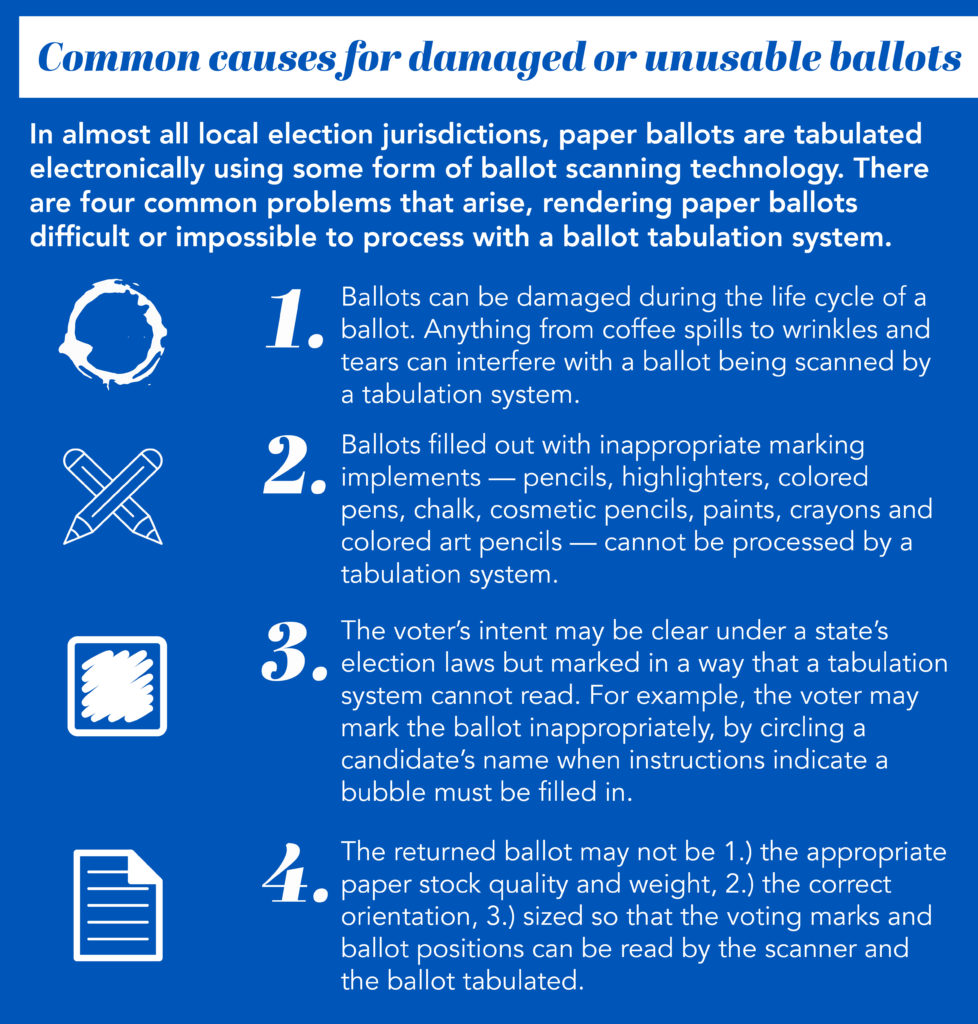

In almost all local election jurisdictions, paper ballots are tabulated electronically, using some form of ballot scanning technology. There are four common problems that arise, rendering paper ballots difficult or impossible to process with a ballot tabulation system.

-

- Ballots can be damaged during the life cycle of a ballot. Anything from coffee spills to wrinkles and tears can interfere with a ballot being scanned by a tabulation system.

- Ballots filled out with inappropriate marking implements — pencils, highlighters, colored pens, chalk, cosmetic pencils, paints, crayons and colored art pencils — cannot be processed by a tabulation system.

- The voter’s intent may be clear under a state’s election laws but marked in a way that a tabulation system cannot read. For example, the voter may mark the ballot inappropriately, by circling a candidate’s name when instructions indicate a bubble must be filled in. Additionally, stray marks on the ballot can interfere with the tabulation system’s ability to scan the ballot.

- The returned ballot may not be (1) the appropriate paper stock quality and weight, (2) the correct orientation (portrait or landscape), or (3) sized so that the voting marks and ballot positions can be read by the scanner and the ballot tabulated.

The last problem occurs most often when voters covered by UOCAVA have requested a ballot electronically and the electronic ballot is printed by the voter. Ballots printed by voters are typically not on paper that is the same weight or size as the paper ballot a voter would receive at a local election office and are often printed on A-4 sized paper, which is the global paper standard size outside the U.S. Additionally, some voters either reduce or enlarge the ballot prior to printing with both actions reducing image quality.

In anticipation of receiving these potentially damaged ballots or those rendered unreadable by ballot tabulation equipment, election officials work to ensure that processes, procedures, trained team members and any desired technology solutions are in place in local election offices before each election.

What ballot duplication is NOT

It’s important to note that the term duplication or replication should not be interpreted as a type of corrupt process to create additional ballots, either voted or unvoted. Ballot Duplication is simply the transcribing of damaged or otherwise machine-unreadable ballots as described above so that these ballots can be tabulated with the others. The ballots cast by UOCAVA, absentee and other remote voters are more likely to fall into one or more of these four problem areas, thus the ballot duplication process is utilized to ensure these ballots will be counted as cast, enabling these voters to exercise their franchise.

Why are we talking about ballot duplication in 2020?

Ballot duplication — or ballot transcription — is part of an election official’s contingency planning process. At its core, ballot duplication is an example of election administration contingency planning in action.

OVI’s December 2019 report, “Examining the Sustainability of Balloting Solutions for Military & Overseas Voting,” noted, “States are under increasing legislative pressure to have contingency plans for all aspects of their election systems, including UOCAVA balloting solutions, due to recent national disasters such as Hurricane Sandy, Hurricane Maria and Hurricane Dorian, and global threats of terrorism, civil disobedience, cyberattacks and mail service disruptions.”

While this report does not specifically mention a worldwide pandemic in its list of global threats, the report’s reference to the importance of contingency planning in all aspects of election administration is all too applicable to the COVID-19 crisis of 2020.

Precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, some states and local jurisdictions have moved to a by-mail or ballot drop-off voting process, either eliminating or reducing in-person voting at a polling place. Others have expanded their absentee voting programs. These states and local jurisdictions are either incorporating no-excuse absentee voting into their voting programs or expanding legally allowable reasons for voters to cast their ballots remotely to include COVID-19 concerns.

As a result, local election officials nationwide may receive higher volumes of ballots in the mail. Many of these ballots may fall into the problem areas described above and thus cannot be read by tabulation equipment. It is safe to say that more remote voting will result in more overall usage of ballot duplication solutions to count these ballots.

This article is the first in a series of posts on the topic of Ballot Duplication. In the next installment, we will share important new recommendations from the OVI Sustainability of UOCAVA Balloting Solutions Subgroup members to help election officials improve their ballot duplication process and hopefully lessen the need for it over time.

Read the other articles in our Ballot Duplication series:

Ballot Duplication: New Recommendations for Contingency Planning in the time of COVID-19 and Beyond

Ballot Duplication Technology: What Is It and How Does It Work?

Continued Advancement in Ballot Duplication Technology Solutions: Pilots in the Field

Contingency Planning During COVID-19: Ballot Duplication in the States

Frequently Asked Questions (and Answers) About Ballot Duplication